Knee Pain & Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS), 5 Common Factors Affecting Patella Alignment

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 09 Sept, 2018

- •

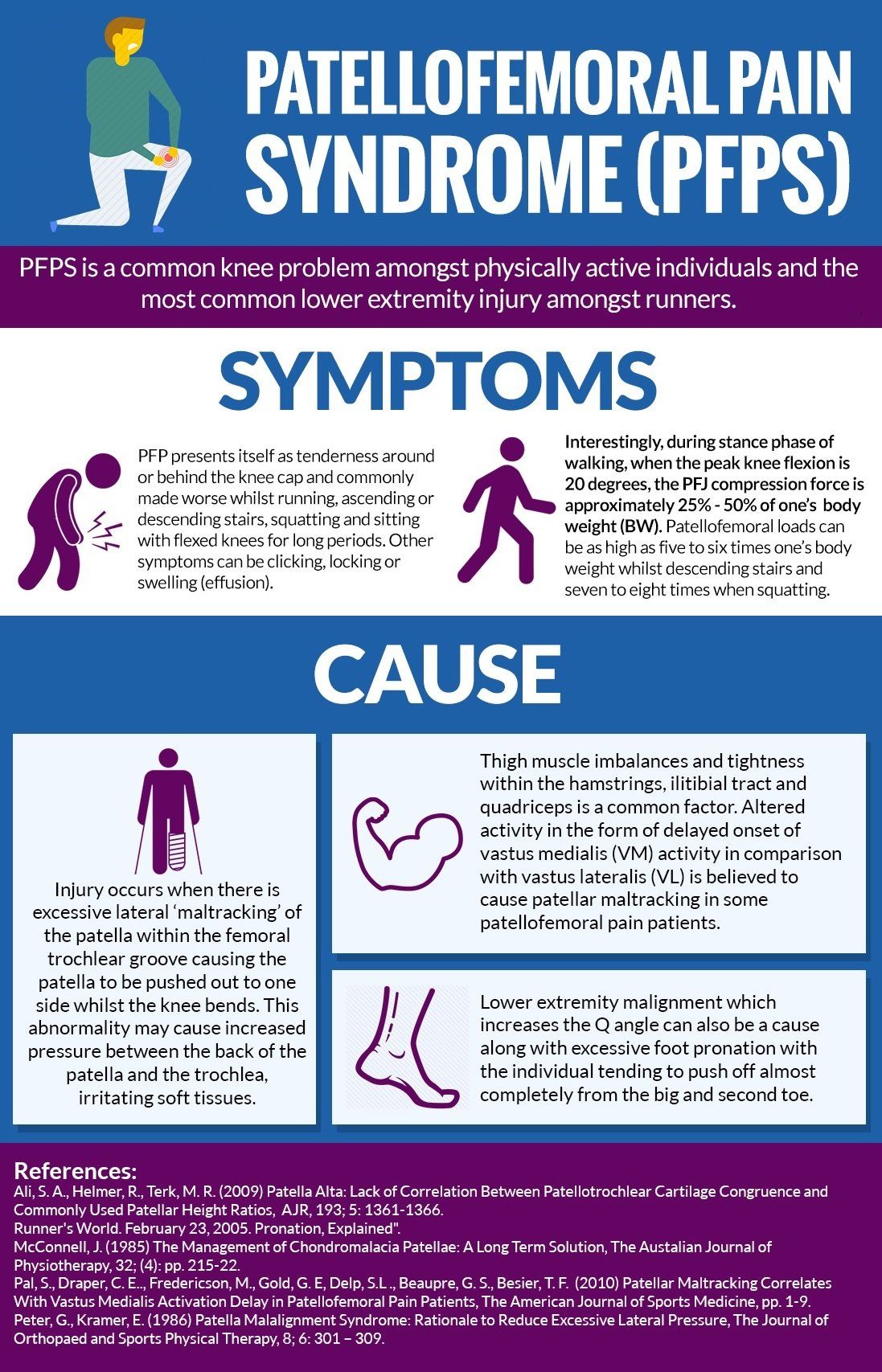

One of the most common knee problems that hobbles its way into clinics is patellofemoral pain syndrome or 'runner's knee'. The condition can also be described as “anterior knee pain”, a term that I personally dislike as it vaguely describes the actual cause of the condition that is being presented to the practitioner.

PFPS mainly affects physically active individuals aged between 15-30 years old (2). Statistically, the prevalence ranges from 21% to 45% in active adolescents, 15% to 33% in adults and is higher in females than males especially in the younger age group (2).

The most reported symptoms related to PFPS are:

- Retropatellar pain (behind the patella/ knee

cap) especially during activities.

- Crepitation (clicking)

- Giving way.

- Pain whilst running, ascending or descending stairs, squatting and sitting with flexed knees for long periods.

The Mechanics of Patellofemoral Joint During Activity are Worth Noting;

The Patellofemoral Joint Reaction Force (PFJRF)

This is the compression force acting on the patellofemoral joint (PFJ) whilst we are active on our knees and increases during knee flexion. The compression force is influenced by knee joint angle and force generated by the quadriceps (muscle tension).

The stress placed on the PFJ is measured by the PFJRF divided by the PFJ joint contact area and is measured as force per unit area.

During stance phase of walking, when the peak knee flexion is 20 degrees, the PFJ compression force is approximately 25% - 50% of body weight (BW).

With greater knee flexion and quadriceps activity such as running and ascending and descending stairs PF compressive forces have been estimated to reach between five and six times our body weight. Deep knee flexion exercises such squatting which require large magnitudes of quadriceps activity can increase compressive forces seven to eight times one’s body weight (McConnell, 1986) .

The greater the contact area between the patella surface and femur, the less stress is placed on the articular tissue. A smaller contact area results in high PFJ stress and may harm the joint meniscus (cartilage) and is made worse for if the patella positioning is poor (Loudon, 2016).

Thus, if the patellofemoral joint structure is malaligned (out of “normal” range) during these movements, one must consider the impact that it will have on the surrounding soft tissue structures.

5 Main Factors Affecting Patella Alignment:

1.)

Increased Q Angle

2.) Muscle Tightness

3.) Excessive Pronation

4.) Patella Alta

5.) Vastus Medialis Obliquus (VMO) Insufficiency

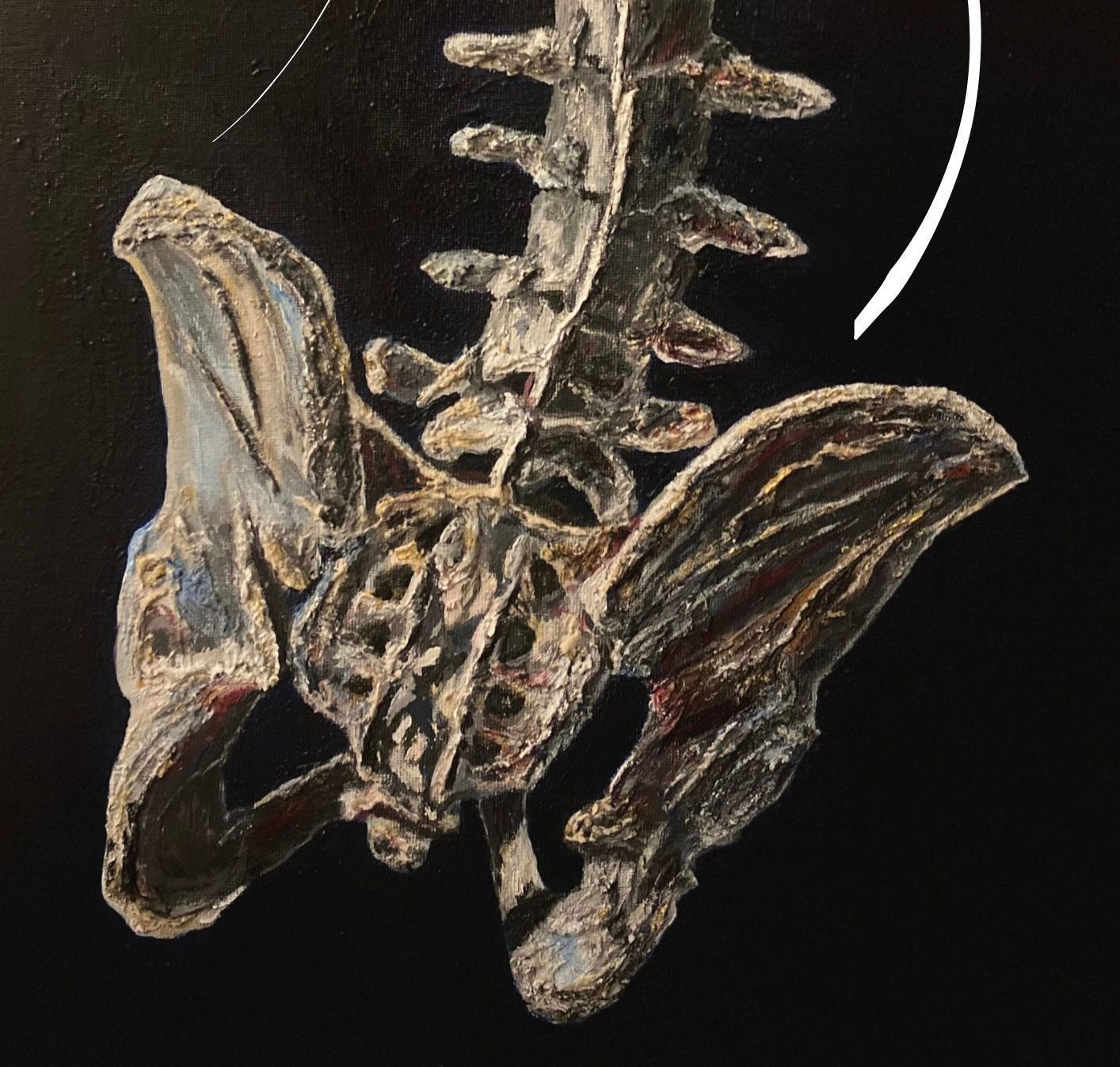

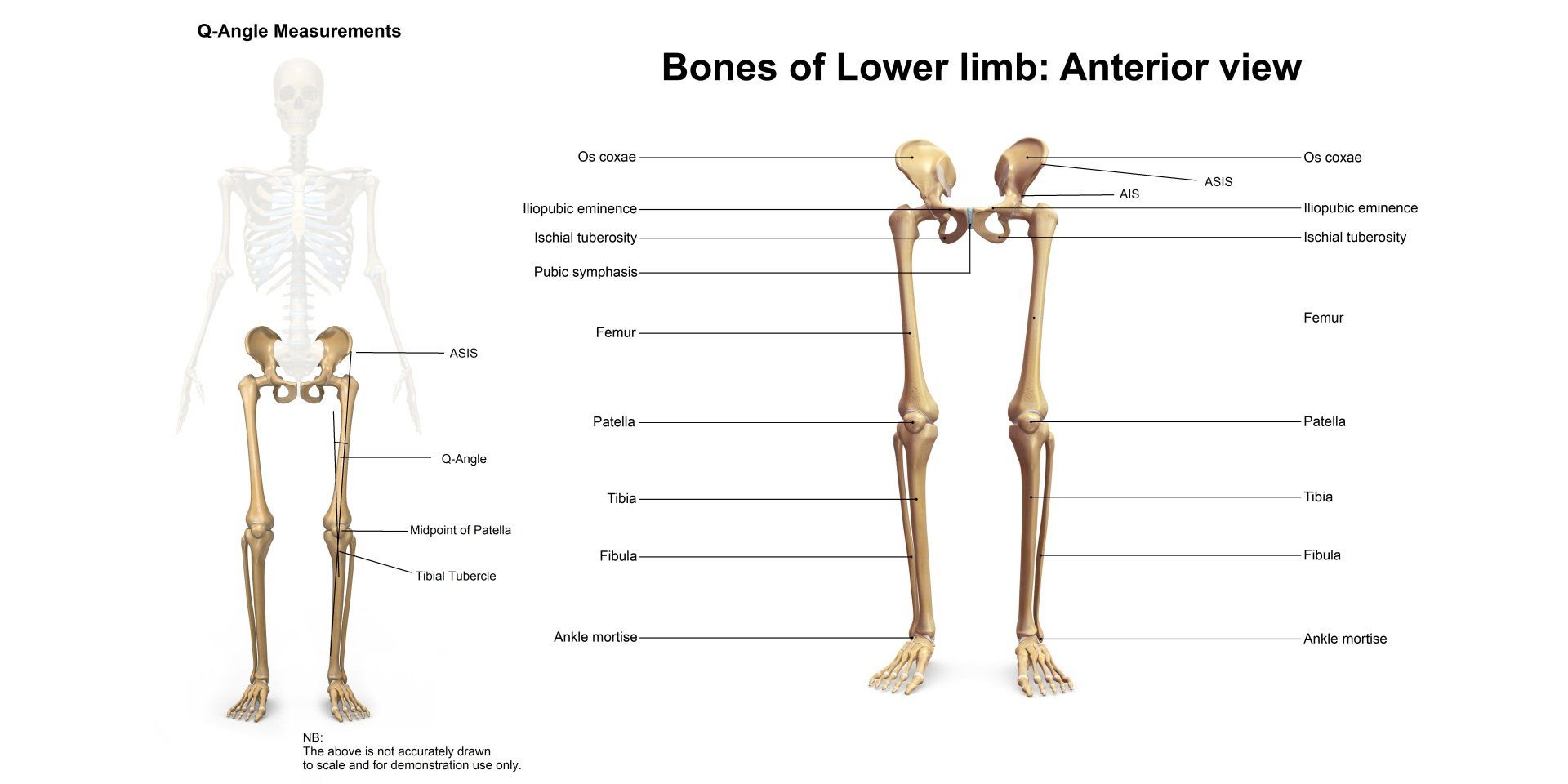

1.) Increased Q Angle

The Q angle is measured by the encounter of two lines; one from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the centre of the patella. The other goes from the tibial tuberosity to the centre of the patella (7). A normal angle is between 10-13 degrees for males and 15-17 degrees for females.

In more recent studies, there appears to be controversy over whether increased Q angle is associated with PFPS (6). One study concluded that runners who had a Q-angle greater than 20 degrees were prone to developing PFPS whilst others concluded there to not be a strong correlation (6).

However, there does seem to be an association with increased Q-Angle and increased lateral patellofemoral contact pressures and patella dislocation (9).

It has been observed that there is a slight Q-Angle difference amongst men and women by only 2.3 degrees which appears to be related to height rather than pelvic dimensions. Shorter individuals in stature tend to have a larger Q angle, indicating that the difference between genders may be attributed to men being taller than women.

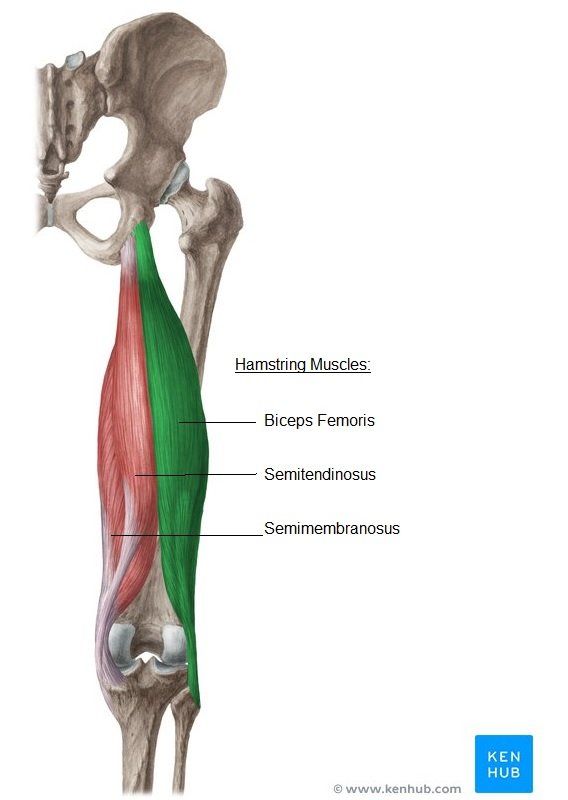

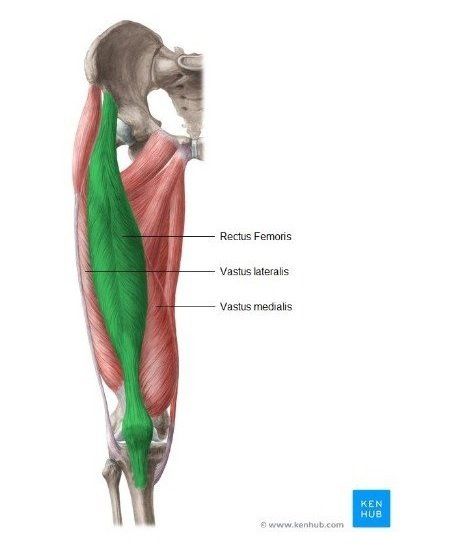

2.) Muscle Tightness

Rectus Femoris; if tight, affects patella movement during knee flexion.

Iliotibial band; if tight pulls the patella laterally during knee flexion.

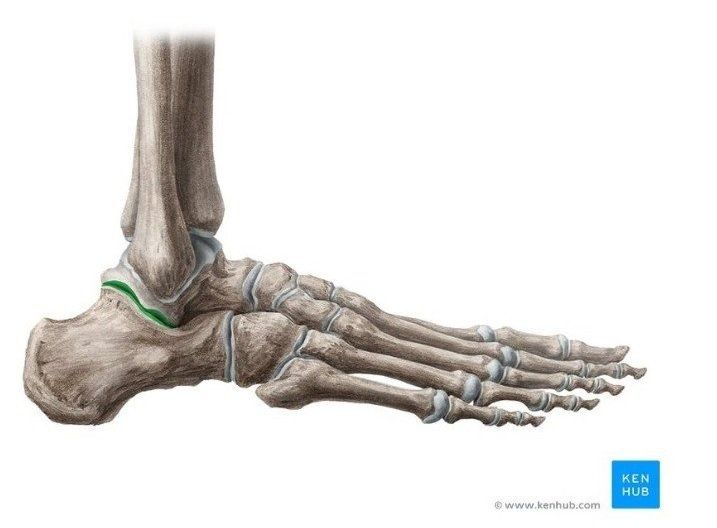

Hamstrings; if tight will cause increased knee flexion which increases the patellofemoral joint reaction force (PFJRF)* during stance. This can cause an increase in ankle dorsiflexion, which can lead to pronation at the subtalar joint as dorsiflexion at the talocrural joint is more occur.

Gastrocnemius; if tight will result in compensatory pronation.

(McConnell , 1985)

3.) Excessive Pronation

Prolonged pronation of the subtalar joint is accompanied by prolonged internal rotation of the tibia causing malalignment of the patella and internal rotation of the femur causing the quadriceps to pull the patella laterally (4).

Other factors that may influence kinematics at the knee are limited dorsiflexion and excessive midfoot mobility (4).4.) Patella Alta or ‘High Riding Patella’

Patella Alta is considered a predisposing factor for the development of patellofemoral pain and is associated with recurrent dislocation of the patella (1). Syed et al., 2009 Report that individuals with patella alta have altered knee extensor mechanics which may predispose them to increased PFJRF.

A high riding patella that is positioned superiorly in height by as much as 8mm can increase the magnitude of the contact force (PFJRF) by 25% and have a reduced contact area by an average of 19% (1). The combined increase of joint force and reduced contact area results in increased joint stress (force per unit area) and thus lead to PFP and chondral injuries in these patients (1).

Patella Baja: If the patella is positioned more inferiorly and sits more lower than ‘normal’, it is termed ‘patella baja’ and might caused from a shortened patella tendon (3).

5.) Vastus Medialis Obliquus (VMO) Insufficiency

Weakness of the VMO has been thought to cause an imbalance of medial or lateral forces acting on the patella and pull the patella laterally in the femoral groove during movement (8). This causes an overload of the lateral aspect of the patellofemoral joint resulting in joint pain and possibly presenting a predisposition for osteoarthritis (8). It is interesting to note that VMO activity is greater with the hip in external rotation.

Single Leg Squat Test: Hip external rotators have been noted to be weaker in PFPS patients whilst performing the single leg squat test. Loading in external rotation whilst performing the actions is known to being beneficial (9).

References:

(1.) Ali, S. A., Helmer, R., Terk, M. R. (2009) Patella Alta: Lack of Correlation Between Patellotrochlear Cartilage Congruence and Commonly Used Patellar Height Ratios, AJR, 193; 5: 1361-1366.

(2.) Clijesen, R., Fuchs, J., Taeymans, J. (2014) Effectiveness of Exercise Therapy in Treatment of Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, PTJournal; 94: 1697-1707.

(3.) Levangie, K. L., Norking, C. C. (2011) Joint Structure and Function, A Comprehensive Analysis (5th Ed.) , Jaypee.

(4.) Loudon, J. K. (2016) Biomechanics and Pathomechanics of The Patellofemoral Joint, TIJSPT, 11; 6: 820-830.

(5.) McConnell, J. (1985) The Management of Chondromalacia Patellae: A Long Term Solution, The Austalian Journal of Physiotherapy, 32; (4): pp. 215-22.

(6.) Peterson, W., Ellermann, A., Goele-Koppenburg, A. et al., (2014) Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, Knee Surg. Sports Traumarol Arthrosc; Springer, 22: 2264-2274.

(7.) Sanchez, H. M., Sanchez, E G de M., Barauna, M. A., Canto, R. S. de T. (2014) Evaluation of Q Angle in Differents Static Postures, Acta Ortop Bras, 22; (6): 325-329 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4273959/

(8.) Sawatsky. A., Bourne, D., Horisberger, M., Jinha, A., Herzog, W. (2012)Changes in Patellofemoral Joint Contact Pressures Caused by Vastus Medialis Muscle Weakness, Clinical Biomechanics; 27: 595–601.

(9.) Waryasz, G. R., McDermott, A. Y. (2008) Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS): A Systematic Review of Anatomy and Potential Risk Factors, Dynamic Medicine, Biomed Central, 7; 9.